- Home

- Jeff Mariotte

City Under the Sand Page 9

City Under the Sand Read online

Page 9

So Aric sat on the floor beside his workbench, where passers-by couldn’t see him from the doorway or the window, and struggled. He was so immersed in the effort that he didn’t hear soft footsteps on the floor, didn’t know he was observed until a sudden, startled “Oh!” alerted him.

“Who’s there?” Aric demanded, closing the book and shoving it into a cubby in the workbench. “What?” He grabbed the bench’s upper surface and hauled himself to his feet.

Rieve stood there, hands covering her mouth. A pink flush graced her fair cheeks. “I’m sorry, Aric,” she said.

“You—you won’t tell anyone, will you?” he pleaded. He was glad it had been her and not a templar, but he didn’t know her well enough to trust her. “I didn’t hear you.”

“I wasn’t certain you were even here. I saw the door open, so I came in, and then I thought I heard you breathing. She touched his arm, just a light, glancing brush. “You were so intent, it was cute. But I was surprised to see you there and couldn’t keep my mouth shut.”

Cute? As in attractive? he wondered. Or the way a baby animal or an infant is cute when it tries to do something obviously beyond its abilities?

“Well, you surprised me in return,” he said. He fidgeted with his coin medallion.

“I didn’t mean to make you uncomfortable, Aric. I know this is terribly bold of me, but I wanted to see you. I didn’t just happen to pass by. I’ve been thinking about you.”

“And I you.” He doubted she had been thinking along the same lines he had. But he would never know unless she told him.

“Do you remember the other day, when my grandfather wanted you to teach me how to use my sword?”

“Of course.”

“Corlan has been trying. He’s quite skilled in it himself. But what he’s not so good at is imparting that skill to someone else. He thinks I should just be able to watch him do something and immediately master it. Perhaps that’s how he learned it, but it doesn’t work that way for me. Then he grows impatient, and we argue.”

“If you’re to be wed, arguing seems bad,” Aric said.

Rieve laughed. The pink had gone out of her cheeks, but her laughter brought it back. Aric envied the color, lying as easily upon her soft skin as sunlight on polished steel. She had always been lovely, but at that moment her beauty snatched his breath away. “My parents argue frequently,” she said. “You’d be surprised at the screaming. I believe some married people elevate arguing from a passing interest to an obsession. But I don’t like it. I have known Corlan since we were children, and been betrothed to him almost as long. He’s a dear friend. None of that makes it easier to be snapped or shouted at.”

Aric couldn’t think of a diplomatic way to ask his next question. “Why tell me this?”

Instead of answering directly, she wandered about the shop, scrutinizing his tools, his small store of metal, even peeking through the doorway into his bedroom. “You have no woman?”

“There have been women,” he admitted. “None who mattered much.”

“I’m surprised, you’re such a handsome fellow.”

He noted that she hadn’t used the word man, which some refused to apply to anyone who wasn’t fully human. “Thank you.”

She spun around to face him again, looking right into his eyes. “Would you teach me? Help me with the parts that Corlan can’t? No one ever has to know. I just want to learn enough that I can convince Corlan he’s actually teaching me something. I can pay you.”

Aric considered this. It would mean spending time with Rieve, a certain amount of close physical contact. Both would be payment enough. “I don’t need your coins—” he began.

She cut him off before he could finish. “When I happened upon you, before I startled you, it looked like you were having some difficulty reading. Your forehead was all wrinkled up like old clothes.”

“I can read a bit,” he admitted. “But that book—parts of it I can’t make out at all.”

“I could help you. You teach me the use of the sword, I teach you how to read better.”

“That’s most generous,” he said. “And I would truly love to accept your offer. But I’m leaving the city shortly. A day, two, perhaps three, I don’t know yet. The journey will be a long one, and I don’t know when I’ll return.”

Her eyes brightened and she put a hand on his arm again. He liked it when she did that. “Where are you going?”

“I wish I knew. Nibenay has asked me to accompany an expedition he’s sending to a lost city somewhere, to look for a trove of metals that might be there.”

“The Shadow King himself asked you?”

“That’s right.” Aric couldn’t help letting pride swell his chest a little. “He said your grandfather told him about me.”

“I am impressed.” She lowered her voice to a conspiratorial level. “He has been generous with some of the noble houses, including ours.”

“He was pleasant enough with me, and generous as well,” Aric said. “But since I’ll be leaving, I can’t promise to teach you.”

“I understand.” Her voice sounded bright, but her expression was crestfallen. “I wish you well on your voyage.”

“Thank you, Rieve.”

She leaned forward, raising herself up on her toes, steadying herself with both hands on his arms. He wouldn’t have minded her staying in just that position for a very long time. Then she pressed her lips to her cheek. The kiss burned there, as if those lips had been made of fired steel. “For your courage,” she said. “And for luck.”

He didn’t know what to say. He wanted to touch the spot she had kissed, but didn’t want her to think he was trying to rub away the trace of her lips.

While he was still searching for some sort of meaningful response, she met his gaze, then turned and hurried from the shop without looking back.

He had driven her away. She had taken the liberty of kissing him, and he had stood there like an absolute fool, saying and doing nothing. And she had realized her mistake and raced out of his presence.

He couldn’t blame her.

He stood looking at the empty doorway, knowing that the best thing that might ever have entered his life had just fled it again, because he had not known how to respond.

Suddenly, he couldn’t wait to get out of Nibenay.

3

Ruhm went drinking with friends again that evening, but Aric couldn’t bring himself to join them. Instead he walked around the city—his city, the only one he had ever known. The one he would soon leave behind. Perhaps he would return, perhaps not. Every traveler told tales of the dangers waiting in the wide world, and the book Aric had tried to read described a landscape full of perils and plagues.

Without the daytime sun blasting the city streets, they were more crowded than during the heat of afternoon. All around him were swindlers, thieves, thugs and killers; people did what they could to survive on Athas, and Aric knew that only a few lucky breaks had made the difference between him having a lawful career and joining Nibenay’s nighttime parade of criminality.

Bundled against the cold, Aric threaded the city’s narrow streets, alleyways and courtyards, passing between pedestrians and kanks and merchant stalls, couriers carrying messages or goods, bands of musicians and dancers, drunks weaving unsteadily between one tavern and the next. Everywhere the eye landed there was something to see: brightly colored clothing, members of every intelligent race known to Athas. Stone walls and cobblestone roadways were intricately carved to display the glorious history of the Shadow King, or else the family histories of those who built the individual structures. Sometimes buildings themselves were the sculptures—here a family home carved in the shape of a face, where one entered through a gaping mouth and looked out upstairs windows shaped like eyes—the “skin” carved still further, with scenes from that family’s past—there an entire block built to represent a cloud ray, its surface carvings representing past defeats of those huge monsters.

Above the streets, people stretched lines

and hung clothing to dry, on those occasions when they had enough water to wash. Higher still, the buildings seemed to meet overhead, sometimes with other walkways far above the streets. There was layer upon layer of life in Nibenay; spires, minarets and turrets everywhere blotted out the stars. Sometimes Aric thought one could live a dozen lifetimes and never see it all.

Music rang from many corners, people singing and playing for their own amusement, small bands and even orchestras and choirs gathered here and there in more organized performances. And Nibenay had its own smell, comprised of blood and sweat and urine, animal dung and ale, the smoke from cooking fires and the oil from lanterns. All of it combined into a single odor that told Aric at every step that he was home.

Since he might never again see the place, he wanted to visit some spots that had been important to him over the years. He would stay far away from the elven market—that place had few pleasant associations, mostly memories of bitterness and strife.

His mother, the half-elf Keyasune, had never left the city either, as far as he knew. She had, in fact, rarely left the area right around the elven market. Her parents had a stall there, selling bolts of fabric obtained from other cities, and her human mother, she said, made blankets and articles of clothing that they also sold. When they were killed, as was often the fate of elves and those who wed them, Keyasune took over the stall. It was there she had met Aric’s father, a human.

“He came in one evening to buy some fine silk,” she told Aric once. He was nine years old, and had been pestering her with questions about his father. She had taken him on a walk, away from the Hill District, out the South Gate and into the desert beyond the city walls. “One of his family’s slaves was a fine seamstress, and his mother wanted silk to have some dresses made. I was alone in the stall, and your father saw my silks and had to have some. It was a wonderfully cool early evening, late in the season of Sun Descending. He tried to bargain the price down, but I held firm.

“While we bickered, though, we were also chatting. There was something about him—his face reminded me of the setting sun, and I smiled just to look at it. He seemed to like me as well. Even after he had paid me for the silk, he stayed and talked. Other merchants glared at us, of course—they are glad to see the coins of humans, but not so receptive to humans themselves.

“When I tried to sleep that night, I kept thinking about him. I later learned he was having the same problem, tossing about his bed thinking of me.

“The next evening, he came back. Same the evening after that. Soon, we were involved in a romance.”

“Yuck,” Aric said. He picked up a rock and hurled it at the city wall, but it fell short of its mark.

“I will spare you those details, Aric. The only reason I’m telling you this is so that you’ll know that once, your father was important to me. He wasn’t just some man I met, but someone I cared for deeply.

“He seemed to like me as well. But it was strange—he liked me, but he hated elves. Never had a good word to say about them. When he was with me, he seemed to loathe himself for being there. If I had been exactly the same person, but not a half-elf, I had no doubt that we’d be wed. But whenever we were together, it had to be in secret, where no one would see us. He stopped coming to the elven market altogether, instead sending me messages when he wanted to see me, and making me meet him elsewhere in the city.

“Then came the day that I had to tell him about you—that I was with child. I feared his reaction, but it was even more explosive than I expected. We had taken a room at an inn, so we could have privacy. But when I told him, he ranted and paced and threw things. Finally the innkeeper knocked on the door to see why so much noise was coming from the room, and your father took advantage of the distraction to storm away.

“I never saw him again.”

“Did you go to his house?” Aric asked.

“He had never told me where he lived. I knew only his first name, but not what family he was from. He had to protect them, he said, from the stigma of having a son who loved a half-elf.”

“What’s a stigma, Mother?” Aric was young, but he understood that telling this story was hard for his mother, could see sadness playing about her lips and eyes, the lines it made in her forehead. He knew, also, that he had forced her to tell it—that asking about him so frequently, and more and more often in the market stall where other elves could overhear, had put her in a position where she had to give him the story. But just this once, she had insisted, and then they’d never speak of it again. He had agreed to her terms, although with a small boy’s uncertain grasp of what “never” might mean.

“It’s something that other people might judge someone for, without knowing the real story behind that fact. What it really meant was that he was ashamed of being with me and didn’t want his family to know about it. And when he learned that he had fathered a child, he wanted nothing more to do with me—with us, really. It was as if he had thought it was all just a game, and it wasn’t until that happened that he knew there could be consequences.

“Anyway, I never saw him again after he left the inn.”

“Really?”

“That’s right. I have no idea if he is alive or dead. Dead, I expect. He was a man of strange, dark moods, and I never expected him to have a long and happy life.”

“How odd.”

“In a way. And then again, not at all odd, but sadly all too common.” She took a path that would lead them back toward the city, and Aric stayed close to her side. “Because he made clear that he wanted nothing to do with our lives, I never told you about him, Aric. And as I told you at the start, I’ll never speak of him again, so don’t bother asking. I’ve given you all the details you need. Your father was a man who loved and hated me at the same time, hated all I was, and it’s for the best that you never knew him.”

After that, whenever Aric wandered the city streets and byways, he wondered if his father had truly died, or had simply avoided the elves. He stared at every older man he saw, those of an age to have been his father, searching for some sort of resemblance to himself. But he never saw any, and the man never returned to make any claims upon him.

He had never felt altogether comfortable in the elven district. His mother had barely been tolerated there, and when she took up with a human man, that tolerance was stretched even thinner. Aric grew up on its outskirts, not part of human or elf society, hated by both. His mother continued to work her stall, and brought young Aric with her, but from an early age he understand the glares and curses and epithets hurled his way.

The first time he touched a metal coin, it came from a human. That had been during Aric’s fourth year. A woman bought several bolts of cloth, planning to make dresses for several daughters, and paid with a metal coin. That was a rare enough event that Keyasune handed it to the boy, so he could see what it looked like. As soon as his tiny fingers touched it, he saw details, in his mind, of the life of the woman who had given it to his mother. He saw her moving with melancholic loneliness through a noble’s estate, thinking about a husband who was rarely at home. Servants cared for two children, both quite young, and she looked in on them, an expression of delight animated her face, but sorrow showed through her eyes. Keyasune, struck by the detail her young son offered, asked a slave she knew who worked for the family, and the slave confirmed Aric’s account.

After that, she tested her son often. He seemed able to do similar things with other metal objects, and in this way he developed his psionic connection to metals. He didn’t know until years later that she had kept the coin, although it represented a great deal of money to her. He had worn it ever since, as his medallion—though when she had presented it to him in that way, she had reminded him that if he was ever in desperate enough straits, it could still be used as currency.

Then, in his tenth year, his mother died. The elves, who had never truly embraced him, banished him from the market. On his own, frightened and hungry and dressed in rags, young Aric tried to make his way in the city,

begging or stealing to keep himself fed, refusing to part with his coin medallion.

Aric went to the chaotic intersection where Cutpurse Lane intersected with Red Mark Alley and Finder’s Alley. The carvings on the walls there showed scenes of an ancient battle, with humanoid soldiers engaged in combat against creatures with reptilian features and long, forked tongues. One of the buildings had a niche cut out of it, at ground level, and for a time, that spot had been where Aric had curled up to sleep at night.

One night, he awoke there to find a bundle tucked up beside him, wrapped in cloth. When he opened it, he was astonished to find clothing in his size, meat and vegetables, and even a few coins. That was the first time he became aware of his mysterious benefactor, and since he knew of few people wealthy enough to give such treasures to a stranger, he decided it must have been a gift from Nibenay himself.

This expedition truly was a gift from Nibenay, although it remained to be seen whether gift was the right word. Assuming he survived it, though—and assuming there really was metal beneath the ruins of this city, because if they didn’t find any, Aric had a feeling he’d be blamed for that failure—it could be the best thing that ever happened to him. He might amass enough wealth to join the nobility. If nothing else, he could enlarge his shop, hire some hands, get work from the kingdom crafting all that new armor and weapons. In any case, it appeared that poverty was in his past now, that from now on he wouldn’t have to worry about how to take on every job that came his way because he could ill afford to turn down a single one.

No, he was certain that at journey’s end, his life would be irreversibly changed. And he was ready for change. He enjoyed working with steel, crafting swords especially. But they were always for someone else. His life was fulfilling, he supposed, in a limited way. Life on Athas was more a matter of survival than fulfillment anyway. But he had a passing acquaintance, through his readings and even the occasional night at Sage’s Square listening to the scholars ramble on, with the works of Athasian philosophers, and he had the sense that there should be more to life than that. There should be some sort of satisfaction with one’s lot, and acceptance that one had done everything he could to live his life to the utmost.

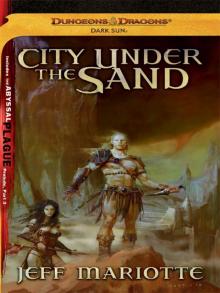

City Under the Sand

City Under the Sand The Burning Season

The Burning Season Sanctuary

Sanctuary Winds of the Wild Sea

Winds of the Wild Sea Serpents in the Garden

Serpents in the Garden Close to the Ground

Close to the Ground Blood Quantum

Blood Quantum Brass in Pocket

Brass in Pocket City Under the Sand: A Dark Sun Novel (Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Sun)

City Under the Sand: A Dark Sun Novel (Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Sun) Witch's Canyon

Witch's Canyon STAR TREK: The Lost Era - 2355-2357 - Deny Thy Father

STAR TREK: The Lost Era - 2355-2357 - Deny Thy Father Dawn of the Ice Bear

Dawn of the Ice Bear The Xander Years, Vol.2

The Xander Years, Vol.2 Ghost of the Wall

Ghost of the Wall 30 Days of Night: Light of Day

30 Days of Night: Light of Day Deny Thy Father

Deny Thy Father Criminal Minds

Criminal Minds Time and Chance

Time and Chance The Folded World

The Folded World Bolthole

Bolthole Narcos

Narcos Right to Die

Right to Die