- Home

- Jeff Mariotte

Winds of the Wild Sea Page 2

Winds of the Wild Sea Read online

Page 2

After a short while, Cheveray himself appeared, bearing a candle in the hand that didn’t hold his cane. He wore white nightclothes and cap, and, with his silver hair and hunched-over posture he looked like some kind of crooked ghost. “Well, children,” he said as he entered the room. “What news? Where is your Pictish friend?”

“We don’t know, Cheveray,” Alanya said gloomily. “He hasn’t returned yet. I don’t know if he’s lost in the city, or captured, or what.”

“Captured?” Cheveray echoed. “You were seen, then?”

“Aye,” Donial replied. “My fault. I sneezed, just as we were leaving. Dust in the air, or something, I guess, but I couldn’t contain it.”

“Rangers gave chase,” Alanya said, taking up the narrative. “Uncle Lupinius is dead. Slain by unknown murderers, though he yet lived when we arrived. But only for a few moments. Long enough to tell us that the Pictish crown Kral seeks has been stolen. We were leaving Father’s house—our house, then, having found my mirror. The house, by all rights, should be mine, and we determined to come back here and talk to you about how to stake my claim. But as Donial said, on our way out we were seen. We split up, to confound our pursuers. Donial and I made our way back here, but we have seen no sign of Kral since.”

“I am sorry about your uncle,” Cheveray said. “In spite of everything that has happened, he was family, after all.”

“I know,” Donial said. His expression was sad, his voice subdued in spite of his apparent agitation. “I feel like I should hate him. But seeing him there, injured. Dying. It was awful.”

“It always is,” Cheveray told them. “Death. We all strive to avoid it, yet finally we greet it, happily or not. I am sure you both were sickened to see your uncle that way, and you unable to help him.”

“We tried,” Alanya put in. “But we were too late.”

“I am certain you did what you could. A most unfortunate situation. As for your friend, he may yet show up.” His warm smile never failed to make Alanya feel better. It did so now as well, in spite of the emotionally wearing night. “It has not been that long, and he is, after all, a stranger here. But he’s also a resourceful fellow, unless I have completely lost the knack of judging character.”

“He is that,” Alanya agreed.

“Then give him a bit more time before you worry,” Cheveray said. He put a calming hand on Alanya’s shoulder, and she pressed it down with her own. “If he is not here by morning, I’ll make some discreet inquiries. Worry not, we shall find him.”

Alanya, as always, took comfort from Cheveray’s steadiness and uncompromising common sense. She still feared for Kral, but she would wait to panic. Maybe, as Cheveray suggested, everything would be put right by morning.

Or as much as could be done, at any rate. Nothing would bring back her father.

Or her uncle.

2

MORNING CAME, WITH no sign of Kral.

Alanya could hardly eat any of the food that Cheveray’s cook put before her. She managed to drink some sweet cider, but her stomach felt like she had swallowed a lead weight.

Kral was missing. Her uncle was dead. It would be impossible to prove that Lupinius was responsible for her father’s death.

And Cheveray’s cook, an elderly gentleman named Paelin, had mentioned as he served breakfast a rumor he had heard: that King Conan was planning to send a large force out to the borderlands to crush the Pictish rebellion growing there.

Alanya knew there was no growing rebellion. There had simply been Kral, one of the last remnants of the Bear Clan, searching for the Pictish crown that her own uncle had stolen from Kral’s people during the attack on their village. Kral had raided Koronaka, sabotaging the construction of a border wall and trying to get information about the crown. He had become known as the “Ghost of the Wall,” since he was never seen by anyone who lived to tell of it. If the rumor of an Aquilonian response was true, it just meant that tales of Kral’s activities had made their way back to the King.

In Kral’s absence the clan’s only surviving woman had taken his place, so even though he was here in Aquilonia, the activities of the “Ghost” continued. Settlers and soldiers had already killed the rest of their village, save one old man.

Surely Conan wouldn’t believe those exaggerated stories. The King had, after all, sent Alanya’s father, Invictus, to the borderlands to expand upon the peace that had been established between Koronaka and the Picts of the Bear Clan. It had been Uncle Lupinius, not the Picts, who had broken that peace, using Alanya’s burgeoning relationship with Kral as an excuse. The settlers had slaughtered the clan, murdering her father along with it. Possibly Conan would send soldiers to exact revenge for her father’s death—but the total destruction of the Bear Clan village would seem to be payment enough.

Donial, she knew, still slept. She hadn’t seen Cheveray this morning, but as she sat alone at the breakfast table, trying not to look at the uneaten meal, he came in from outside.

“I have put some inquiries into motion,” he told Alanya. “If Kral has been arrested or detained by any authorities, civil or military, we’ll find out about it soon enough. Further, I’ve started some of my associates researching the details of your father’s estate. We shall have you set up in that house in no time.”

“Thank you, Cheveray,” Alanya said. She was sure she didn’t sound very heartened, however.

“What’s wrong?”

“All that,” Alanya said. “And more.” She told Cheveray about the rumor she had heard from Paelin. “There is no Pictish invasion,” she insisted. “That’s just stories blown out of proportion.”

“Well, then, if King Conan does send an army, that is what they shall discover,” Cheveray suggested.

“Perhaps,” Alanya said. “But maybe they’ll decide that as long as they have traveled so far, they might as well go ahead and kill the rest of the Picts.”

“Never had much use for them myself,” Cheveray said. “But your friend Kral seems decent enough.”

“He’s wonderful!” Alanya retorted. “If not for him, I would not be here now. I would still be trapped in Koronaka. Or more likely, dead on the road between there and here.”

“Then we all owe him a debt that can never be repaid, Alanya,” Cheveray said, with obvious sincerity. “For you are truly a special young lady, and one without whom the world would indeed be a far grimmer place.”

Alanya smiled in spite of herself. “Can you talk to the King, then?” she pleaded, the quick grin already fading. “If there is war between Aquilonia and the Picts, then all my father’s work, and his death, will have been in vain.”

Cheveray looked serious when he answered. “I will try,” he promised. “But I can make no guarantees. If these events have already been set in motion, it will be most difficult to bring them to a sudden halt. The course of history flows only one way, child, never forget that. That is why it’s easier not to make a mistake in the first place than to take it back once it has been made.”

Alanya swallowed and nodded. It had, she supposed, been her bad judgment, leaving Koronaka by herself to go off into the woods, that had started this entire chain of events. That’s where she had met Kral, and they had become friends. And where they had been observed by Donial. Uncle Lupinius had used that as an excuse to raid the Pictish village, killing everyone they found. Things had escalated from there, with the result that her father and uncle were dead, and so was virtually everyone Kral had ever known.

The only consolation—and it was scant indeed—was that she was home, back in Tarantia, and that her father’s residence, the house in which she had grown up, would soon be hers. She and Donial would live there together, with whatever fragments of their father’s staff they could persuade to stay on. Kral could have a place there, too, if he wanted. She suspected that he would not make that decision. Once he managed to reclaim the Teeth of the Ice Bear crown, which Lupinius had stolen from his clan, he would return it to its proper place in the Pictish wilderness

and stay there to rebuild. Kral cared little for cities or civilization. It was obvious from his every word and gesture since he’d been in Tarantia that the place was far too large and crowded for his liking. He was a true child of the wilderness and would never be happy, Alanya believed, unless he was surrounded by trees and rivers and the creatures that dwelled there.

They were what they were—she a city girl, born and bred in Aquilonia’s heart, and he a barbarian from the dark forests of the far west. If she could find him again—when she found him, mentally correcting herself, determined to remain optimistic—she would just have to enjoy his company for as long as they were together. The gulf between them was too wide to be spanned forever. Ultimately, they would stand on its opposite sides.

She took another sip of cider, nibbled halfheartedly on a biscuit, and wondered where he might be.

TREMONT’S FINGERS WERE nearly as long and thin as the dagger he wielded. He was a thief, who the night before had posed as a wealthy nobleman named Declariat. Thus he found himself in possession of that which he had stolen: a worthless-looking, barbaric crown made of bones and teeth. He had acquired it at the behest of one Bresson, to whom he often sold stolen goods. But once Bresson saw what he had sent Tremont after, he wanted no part of the thing. Which meant that Tremont had murdered two people and put himself in considerable jeopardy for nothing.

Well, he was not willing to let it be for nothing. The teeth with which the crown was embedded were unusual, for their size if nothing else. It was his intention to pry them loose and sell them as curios. That would net a few coins, at least. Then he could sell the bone framework to someone else. Someone like the very man he had pretended to be, who did indeed have a reputation as someone who collected examples of barbaric handiwork. Since the man had never seen the crown with the teeth in place, he would likely pay just as much for it without them as he would have with them. That way, Tremont could pocket a little extra for the odd, huge teeth. And if Declariat wouldn’t pay for the crown, someone else would.

Tremont didn’t stand to make a lot for his night’s work. He seldom did. He got by, stealing a little here and a little there. His apartment was small and crowded. Most nights, someone with even less luck than he slept on his doorstep. The building was far from peaceful, with the sounds of fighting and love-making and the constant battle against vermin always filling the air. Tremont was lean by nature, but that trait was made more pronounced by the fact that sometimes entire days would go by without a meal. Other days, his meals would consist of whatever scraps of food he could scrounge. Bresson had tried to help, by steering him to the crown, and now Tremont was determined to realize something for his troubles.

Tremont’s stomach growled as he poked at the teeth, trying to work them loose from the fine copper wire that held them in place. He would feast tonight.

One way or another.

THE CELL IN which Kral found himself was dank and dark and smelled horrible. It was just wide enough for him to lie down in, but if he stretched his arms over his head, he could touch both sides of it at once. Not that he wanted to lie down on the floor. He had a feeling it had been a very long time since it had been washed.

In the wilderness, the ground was constantly replenished. Wind and rain scoured the earth. But here, in the tiny cage deep underground, the elements never reached. Kral wanted to pace, but with only a couple of steps he was as far as he could go. He felt as if he would explode if he had to stay there for very long. Being caged was the worst thing that could happen to a Pict—far better to have died in battle, painted and screaming for the heads of his enemies.

He had been taken to the city guardsmen by the Aquilonian soldiers. They had peppered him with questions about Lupinius’s murder, to which he had replied with a version of the truth. He had sought an object stolen from his people. The Ranger had been dead when he arrived, and Lupinius murdered. He had called for help, to which the Rangers on hand at the estate could attest. Lupinius had died before anyone had arrived. All he left out was the presence of Alanya and Donial. When the guardsmen told him the Rangers had insisted they chased three, not one, Kral simply held firm, saying they were mistaken. After all, if they chased three, where were the other two? Were they saying he was the easiest to catch?

Later that night, two guardsmen bearing torches had led him down a winding staircase and past a series of barred doors to his cell. Behind some of those doors he heard snoring or bizarre mutterings, and he wondered how long some of these people had been here.

He believed it was morning, but there was no real way to tell. No light from the sun reached the cell. He could hear more of his fellow prisoners moving about than he had during the night, and he was sure several hours had passed, during which he had slept only fitfully on the straw ticking provided.

He sat on the straw, knees bent, forearms resting on them. He would wither away and die there. And since he had killed an Aquilonian soldier, he had little doubt that he was fated to do exactly that.

Unless they took him out and put him to death first.

Kral felt hopelessness descend on him like night over the forest. He had failed to find the Teeth and return it to its home in the Ice Bear’s cave. What the result of his failure would be, he didn’t know. He could only speculate that it would be disastrous for the Pictish people, or the crown would not have been so carefully tended for all these generations.

He would probably never again know the forests and fields and mountains of his homeland, never again feel the freedom of running between the trees, with no company but birds and sky. He tried to hold out hope that Alanya would somehow find him here and rescue him. But he knew, deep down, how unlikely that was. Even if she did discover his whereabouts, how could she free him? She was no warrior, to break into a prison and liberate its inmates. Neither was Donial, or Cheveray for that matter. And they were Aquilonian, after all, so breaking their own laws to get him out would not be something they would do lightly.

No, he had to stay alert for any possible chance to get himself out of here. But failing that, he had to allow for the likelihood that these dark walls and barred door would be the last things he would ever see.

“You in there,” he heard a voice say. Older, male, raspy. “I can tell by your breathing that you’re awake. Tell me, what of the world outside? Is the Cimmerian still king, or has the Aquilonian nobility risen up to depose the barbarian?”

“If you speak to me,” Kral answered, “and you refer to Conan, then yes, he still reigns. I saw him myself. It was only last night, though it seems a year or more.”

“You are no Hyborian,” the voice said.

“I am Kral, a Pict.”

“A Pict?” Surprise was evident in the aged one’s voice. “Yet you speak our tongue.”

“I said I am a Pict, not that I am stupid,” Kral protested. “Yes, I speak your tongue.”

“Your accent is terrible,” the man said. “But I can understand you. How do you come to be in here?”

“I was being chased by some Aquilonian soldiers—over a misunderstanding—and defending myself, killed one of them.”

“They do not take that lightly around here,” the man said.

Kral had not expected that they would. “How long have you been in here?”

The man hesitated before answering. “Honestly, I know not,” he said. “Conan had not yet taken the throne when I was arrested. I remember that much. I killed, as well—two men, in fact, who had cheated me in a game of chance. Or I believed they had. I was more than a little drunk, so I am not altogether sure.”

“So . . . you have been here for years,” Kral said. “And they have not executed you for your crimes but just left you to rot?”

The man chuckled, a wet, unpleasant sound. “That about sums it up,” he said. “Often, I suspect they have forgotten I yet exist.”

“I never forget you’re here, Totlio,” another voice called.

“That’s Carillus, our jailer,” the old man called Totlio explai

ned. “Carillus, be kind to our young friend here. He is not from these parts.”

“I could tell by the accent,” Carillus said. Kral couldn’t see him from where he sat, and preferred not to get up and go to the door just now. Carillus sounded much younger than Totlio, and healthier. “Where are you from, dog?”

“He’s a Pict,” Totlio answered before Kral could.

“A Pict? Good Aquilonian, then, for a savage.”

Totlio chuckled again, and it turned into a rasping cough. “Don’t get him started,” he said when he was able. “He’ll tell you that savages can learn languages just as well as any of us.”

“We can,” Kral declared. “I can speak your tongue, yet I have not heard either of you speaking Pictish.”

Carillus joined in Totlio’s laughter. “You make a good point,” he said. “I think I will enjoy having you around, young Pict. Maybe we will get to keep you for a while.”

Kral couldn’t think of anything that would be worse.

3

A DAY HAD passed, then another. Lupinius’s body was on display at the house, prior to its cremation. Alanya and Donial had agreed with Cheveray’s suggestion that they not visit the body or the house during that time. Alanya’s feelings about it were mixed, confused. He had been family, as much as she had hated him at times. Her last surviving family, besides her brother. But she still believed he had killed her father. Cheveray had speculated that if Lupinius’s Rangers, who knew them both, saw them in Tarantia, they might be held as accomplices in their uncle’s murder. Chances were they had captured Kral and already guessed that Alanya and Donial were responsible for his presence in the city.

There had been no word of Kral. Cheveray insisted that his people, whoever they might be, were working on reclaiming Alanya and Donial’s house for them and working on finding out what had become of Kral.

City Under the Sand

City Under the Sand The Burning Season

The Burning Season Sanctuary

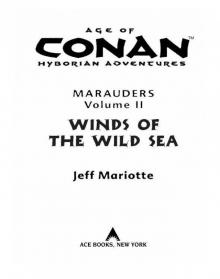

Sanctuary Winds of the Wild Sea

Winds of the Wild Sea Serpents in the Garden

Serpents in the Garden Close to the Ground

Close to the Ground Blood Quantum

Blood Quantum Brass in Pocket

Brass in Pocket City Under the Sand: A Dark Sun Novel (Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Sun)

City Under the Sand: A Dark Sun Novel (Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Sun) Witch's Canyon

Witch's Canyon STAR TREK: The Lost Era - 2355-2357 - Deny Thy Father

STAR TREK: The Lost Era - 2355-2357 - Deny Thy Father Dawn of the Ice Bear

Dawn of the Ice Bear The Xander Years, Vol.2

The Xander Years, Vol.2 Ghost of the Wall

Ghost of the Wall 30 Days of Night: Light of Day

30 Days of Night: Light of Day Deny Thy Father

Deny Thy Father Criminal Minds

Criminal Minds Time and Chance

Time and Chance The Folded World

The Folded World Bolthole

Bolthole Narcos

Narcos Right to Die

Right to Die